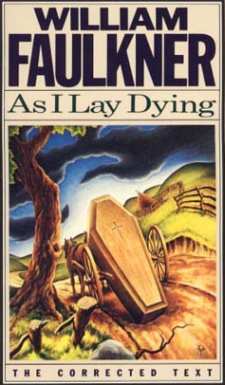

William Faulkner wrote his fifth novel, As I Lay Dying, in only six weeks in 1929. It was published after very little editing in 1930. The novel tells the story of the Bundren family traveling to bury their dead mother. The novel is famous for its experimental narrative technique, which Faulkner began in his earlier novel Sound and the Fury: fifteen characters take turns narrating the story in streams of consciousness over the course of fifty-nine, sometimes overlapping sections. At the time, Faulkner’s novel contributed substantially to the growing Modernist movement. He was no doubt influenced by the work of Sigmund Freud, whose theories about the subconscious were made increasingly popular in the 1920s. Faulkner’s novel regards subconscious thought as more important than conscious action or speech; long passages of italicized text within the novel would seem to reflect these inner workings of the mind. Faulkner’s prolific career in writing is marked by his 1949 Nobel Prize in Literature and two Pulitzer Prizes, one in 1955 and the other in 1962.

Why Should I Care?

As I Lay Dying might be one of the most important works in American Literature, but it just sounds to us like the greatest of all childhood games: The Oregon Trail. But let us demonstrate:

- Rations are low.

- You have set your pace to grueling and your prose to convoluted.

- Someone has died (though not of dysentery).

- Ford the river, or caulk the wagon and float it?

- Bad choice. You lost 2 mules, a leg, clarity of plot, some farm tools, and all the optimism you had left.

Chuckle. We knew this book would be easy.

- Wait a minute.

- You are crazy, according to one member of your party.

- You are the most logical guy around, according to you.

- You’re a threat, according to another member of your party.

- Someone is pregnant (and unmarried).

Whoops! That reminds us to tell you that As I Lay Dying features no fewer than fifteen different narrators, which can complicate the heck out of any trail you’re traveling, Oregon or not. Even the most basic of stories – a journey from location A to location B – is actually a patchwork of perspectives, opinions, and points of view.